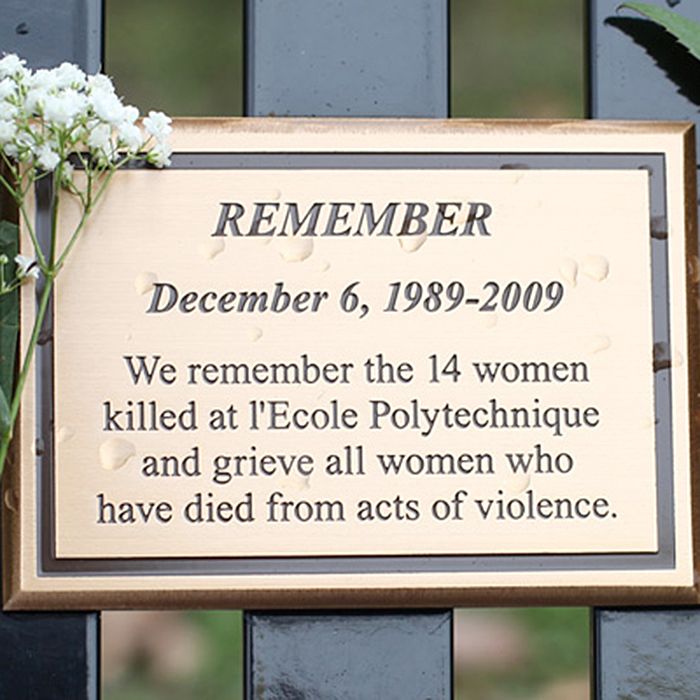

First of all, please accept my profound apologies for my ability to attend the ceremonies in Chatham this year to mark what is the most important anniversary on my personal calendar, a tragedy that marked me for life – the massacre at the Ecole Polytechnique on Dec. 6, 1989.

In recent years, I have returned again and again to the lines the great poet Sylvia Plath wrote in a poem called, “Words,” a poem that reminds me how inadequate mere language can be at times like these. This is the last stanza of that poem:

Dry and riderless,

The indefatigable hoof-taps,

While

From the bottom of the pool, fixed stars

Govern a life.

A quarter-century has passed since that night and the emotions remain as raw as they were then and as far beyond the power of language to express. For years afterward, I chastised myself for my inability to find a way to express the agony of what happened. No matter how I phrased it, the words (those “dry and riderless” words, in Sylvia Plath’s phrase) seemed so hopelessly inadequate, mere filigree eloquence shattered on the rock of tragedy.

Eventually, I had to accept that I would never find the phrases I sought, that such words do not exist in any language. But the story must be told.

The impressions are indelible: The cold drizzle that turned to snow. The glare of streetlights on wet pavement. Feet gone cold as stone. The row of ambulances idling, waiting, exhaust wafting into the night air. Police officials dashing into the vast building that loomed over us, the horror within still a secret.

By sheer coincidence, I was one of the first reporters to arrive at the École Polytechnique late that December afternoon. There was a radio crew already there, a print reporter or two, a television crew just arriving. We were in time to see the wounded brought out of the building, what seemed like an endless parade of stretchers.

During the interminable wait on the hill, we ran the gamut of emotions. Oddly, the sheer number of wounded convinced us that there would not be much more in the way of bad news: if all these victims had survived, surely the killer or killers could not have hit many more. We told ourselves there would be three dead, two dead, perhaps only the killer himself.

Then someone noticed that long row of idling ambulances. They were not there for decoration. Something truly horrible had happened inside that building. Not long after, it became official with the announcement: “There are 14 dead – and they are all women.”

There was no delay in grasping the import of that statement. This was an engineering building, a place where female students would be a tiny minority. The killer had sought women, hunted them down, killed them (italics, please) because they were women. (end ital.) Even then, mass killings had become all too common – but killings on this scale, triggered by a lethal misogyny? The effect was utterly devastating.

We live in the age of disposable public grief, orchestrated on television in living color, with talking heads telling us what we’re supposed to think and feel. Shock and horror Tuesday, mourning Wednesday, and we’re supposed to be over it by Thursday. The sheer repetition of the images of tragedy – towers falling, school shootings, natural disasters – numbs the senses and robs our emotions of any sense of genuine grief. In our 24/7 news cycle, new tragedy nudges the old off the front pages before we have even begun to comprehend what just happened.

But the only possible response to the massacre at the Polytechnique is a raw, enduring grief. It (italics, please) should (end italics) wound us to the core, because if it doesn’t, we are less than human. If we don’t feel that sorrow and feel it deeply, we won’t act.

After we had learned the extent of the tragedy that awful day, after we had gleaned all we could on the hill where the wet snow was still falling, after I had walked all the way around that dark and massive building trying to imagine what had happened inside, we somehow made our way back to the newsroom to write our stories, working on auto-pilot, putting aside our own feelings long enough to get the job done.

It was well past midnight by the time I had written and rewritten my column and done telephone interviews with multiple news outlets. In need of a place to decompress, I made my way to our hangout in Old Montreal. There, somewhere near closing time, I finally broke down, repeating over and over a hopeless litany that still echoes through the years:

“They were so young… they were so young… they were so young.”

[…] Todd, who had hoped to attend the Chatham event, suffered a back injury and was unable to travel. He was one of the first reporters on the scene 25 years ago. To read Todd’s full message, click here. […]