Jenna Cocullo, Local Journalism Initiative

Solutions to the Erie Shoreline flood and erosion problems will have to be solved with resilience, not in-water structures, consultant Peter Zuzek pointed out at Monday night’s meeting.

The Chatham-Kent Lake Erie Shoreline Study, prepared by Zuzek Inc., was released on April 24, detailing anticipated risks and coastal hazards due to climate change.

On Monday, council held a virtual meeting to go over the report with Zuzek and answer questions from the public.

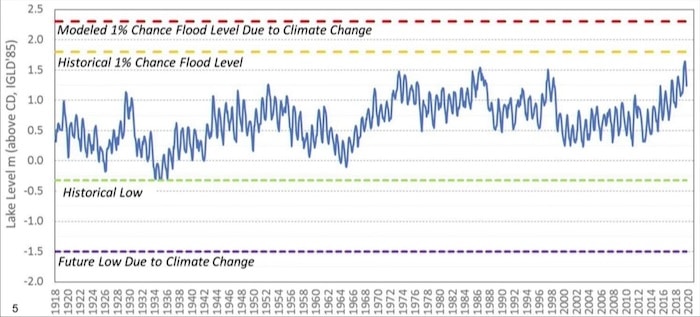

This past June, Lake Erie saw all-time highs for mean lake levels in a singular month, reaching almost two metres above normal levels.

Lake ice is already declining to the point where around 2080, there could be no ice at all, Zuzek said. The study found that no ice means erosion rates will increase by 70-120 per cent. As well, winter wave energy storms would impact the shorelines, depending on the areas.

“This is something we are quite concerned about from the standpoint of increasing exposure to the communities to the effects of storms during the winter time,” Zuzek said.

Zuzek expects “even higher highs in the future” and said water levels cannot be regulated as there is currently no structure on the lake that can be used to moderate them.

“It is a natural system. The levels go up and down in response to supplies from the Detroit River as well as all the local tributaries,” he said.

Zuzek said there have been numerous studies looking into building a structure to moderate the lake levels, with many of which he has been involved. Reports dating back to the 1930s to the present day have all concluded that structural intervention cannot be further pursued.

The International Joint Commission, an organization established by the United States and Canada to resolve water issues, has historically said it is not pursuing any structural intervention.

Zuzek said that “the message was pretty loud and clear” that there is no intention to moderate levels in the Great Lakes. He also pointed out that Lake Ontario, which is moderated by a dam, has also seen historically high levels in recent years.

“We need to focus on communities building resilience and not counting on them to build more structures,” he said.

In the report, breakwaters and tetrapods were not considered to dissipate waves because they are the most expensive option to construct. Wind energy can still find its way between gaps in the breakers, which means the solution would have to be combined with further protection on the shoreline.

READ MORE: ADAPTION FOR ERIE SHORELINE CAN COST UP TO $217M: ZUZEK REPORT

Tetrapod wave breaks also work best in shallow locations with a lot of sand supply, however, the most vulnerable areas of the shorelines are made up of clay.

Zuzek also said that the bottom of the lake also erodes so if something were to be put on the bottom, there is no guarantee that it will be there in a year from now.

Rondeau and Federal Navigation Channel

The trends identified in the report for Rondeau Provincial Park have not been positive.

“Everything is eroding back into the bay, but the sand itself is migrating back into the navigation channel,” said Zuzek.

Since 1955, more than 160 hectares of marshland has been lost near Rondeau Park due to retreat of the area and increased exposure to wave energy.

Because the east jetty is no longer connected to the barrier beach on the island, sand is filling into the gap, lining the channel with sediment, increasing exposure to the field dock and commercial fishing.

Breaches in the barrier beach have increased to the point where shallow boats can be driven through. Zuzek said the barrier would keep moving to the point where the rift might disappear altogether.

For the community, that means in the deep part of Lake Erie off Rondeau, wave heights can increase to at least 2.7 metres inside Rondeau Bay, infringing on communities and impacting wildlife and wetlands.

Currently the Rondeau Bay Estates is a success story because the houses were constructed above the 100-year flood levels, but when climate change levels are taken into account, it may face danger.

Erie Shore Drive and Erieau

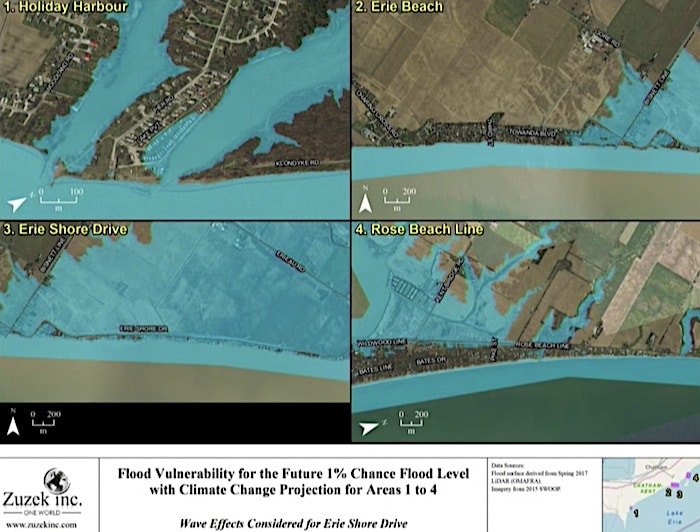

During an extreme storm, Erie Shore Drive can see water depths of 4.3 metres, compared to depths of 2.2 metres in 1938.

“With this type of information we’re able to characterize that increased risk exposure to places like Erie Shore Drive, and others within the study area, and factor in how climate change is making areas already vulnerable to coastal risks even more vulnerable moving forward,” Zuzek said.

The extent of the flooding can reach 563 hectares of water flowing across the entire barrier system because it is relatively low lying compared to other areas across the shoreline. That number increases to 647 hectares when climate change levels are taken into account.

If the dykes were to breach, a metre or more of water would inundate the road to Erieau, making it impossible for even emergency vehicles to pass through.

“This is a very serious concern when you can’t get emergency vehicles in and out. And you can’t get people in and out. It’s a very serious concern and risk to the community,” he said.

More than 475 homes, totalling $44 million, are at risk of being affected between Erie Shore Drive, Erieau, Shrewsbury and The Summer Place, almost doubling when climate change numbers are taken into account.

Talbot Trail

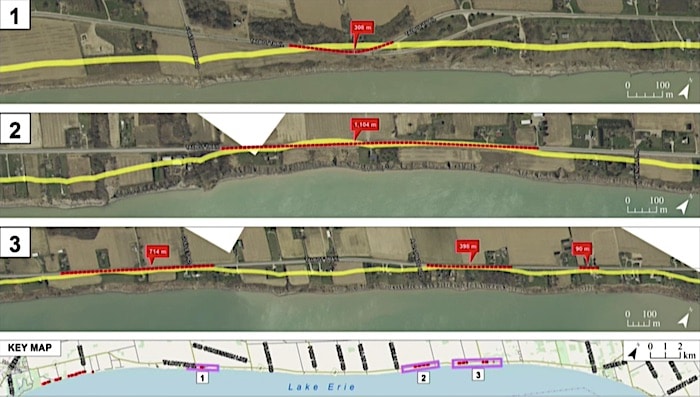

Thousands of metres of roads are impacted within the next 50-year planning horizon for Talbot Trail. Projected decrease in ice cover can even further accelerate the lines.

The numbers do not take into account climate change because the study used information available from 2015 which did not factor in the most recent accelerated erosion along the shoreline.

Zuzek said they will be gathering information with the conservation authority once it is safe to do so after the pandemic. Zuzek said they received more funding from the Ministry of Environment, Conservation and Parks, allowing them to continue their effort with the municipality until March 2021.

Regardless of low water levels, the land will continue to erode.

“There is no holiday from erosion,” Zuzek said.

In total, Zuzek said a “do-nothing” approach to the erosion problem in high bluff areas can cause around $69 million in infrastructure losses with 500 buildings affected between Wheatley Park to Campbell Road, Talbot Trail (between Campbell Road to Charing Cross) and the bluffs east of Rondeau Park.

Assessment of the vulnerabilities in the study did not include damage to interior contents of the buildings, loss of nearby agricultural crops should dikes breach, or the social impacts of natural disasters.

“This is not to suggest that these are not important things. We just chose to focus on the traditional elements so we can work toward getting quickly to the adaptation aspects and focus on solutions,” Zuzek said. “But certainly these types of natural disasters cause disruption to local businesses with a lot of secondary impacts.”

Zuzek said the maps in the report were not generated at a scale able to help individuals evaluate a single lot for their homes, but there are plans moving forward with the conservation authority to generate that kind of information.