To Chatham native Meaghan Creed, the brain is a puzzle. Her quest for solutions has taken her to Switzerland and now Maryland.

Creed, 30, is turning heads with her research into addiction. Currently an assistant professor in pharmacology at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, she recently earned the Science & PINS Prize for Neuromodulation.

Last year, she received the Pfizer Prize for Young Scientists.

The awards are for her research into addiction and its impact on the brain.

Creed grew up in Chatham, attending first McNaughton Avenue Public School and then Chatham-Kent Secondary School, before heading off to the University of Toronto.

It was at McNaughton Avenue PS when she became particularly interested in biology.

“I think I always wanted to be a scientist. I remember a career day in Grade 2 and a scientist came in to talk about genetically engineered corn,” she said. “Biology has been my interest since that second-grade career day.”

She credited a trio of high school educators for honing her interest.

“I really had excellent high school science teachers: Robin Shepherd, George Argenti and Dave Page,” she said. “My physics, biology and chemistry teachers were pretty formative.”

At the U of T, Creed earned first her Bachelors of Science and then her PhD in pharmacology and neuroscience.

From there, she moved to Switzerland for four years for extra training.

Creed now lives in Washington, DC, and does her work at the University of Maryland. Her husband, also a scientist, works in nearby Bethesda.

Creed said the Pfizer award goes to a “young” scientist – anyone under the age of 45.

She earned the award while at the University of Geneva for her work implanting electrodes into the brains of mice to treat addiction.

The Science and PINS Prize this year is for similar research.

Creed said while working on her PhD, she studied dopamine, a neurotransmitter in the brain. It helps control the brain’s reward and pleasure centres. It also helps send messages to other parts of the body, telling them when and how to move.

Parkinson’s Disease, Creed said, negatively impacts a person’s dopamine levels, and that contributes to motor control impairment.

That comes from having too little dopamine. Having too much, which is what can occur from using addictive drugs, Creed said, also has long-lasting effects on the brain.

“Dopamine has been the theme,” she said of her research. “What does it do to the brain? How does it change behaviour?”

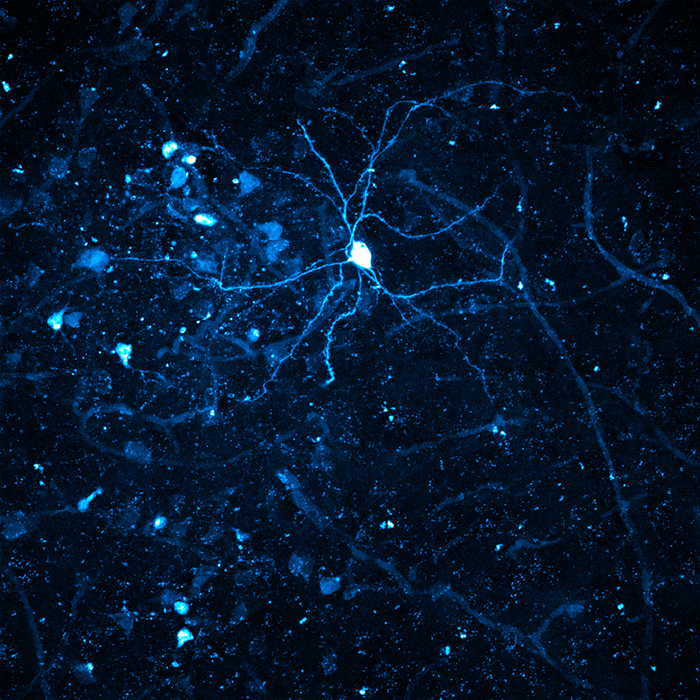

In the case of addiction, Creed has worked with mice. Researchers give the mice cocaine and document the changes in the brain’s reward circuit.

“There are definitely neuro changes that take place when you take these addictive drugs. We’re able to show these specific changes,” Creed said. “The reward system is normally there to guide us to do things that are important for our survival – food, partners, social contact, etc. Addictive drugs hijack the circuitry and activate it in a more addictive way. Taking the drug is more rewarding than other things – food, relationships. Your whole reward system is geared towards finding and consuming drugs, above all else.”

In her research, addicted mice are treated with deep brain stimulation protocol where the rodents have electrodes put into the area of the rewards system and it is turned on for short periods of time, and a drug that is used to treat Tourette Syndrome is administered. The results speak for themselves.

“We give the stimulation for 15 minutes. The next day, they behave like mice who have never seen cocaine before,” she said. “Their brains look like normal mice brains rather than ones that were exposed to cocaine.”

Deep brain stimulation does exist for humans. It’s mostly used to treat Parkinson’s disease, she said. In fact, there are more than 100,000 people around the world who have pacemakers for their brains specifically to help control their Parkinson’s.

Creed said there are also cases where people have had the pacemakers put in to help battle addiction as well.

According to published research material, if you stop the brain stimulation, the symptoms return, requiring the pacemakers to always be on.

Creed said the protocol she’s working on could prove to be much more effective.

The Chatham native is turning her focus to opioids, a growing addiction around the globe, including here in Chatham-Kent.

“The (opioids) release more dopamine than morphine. They can be more addictive than morphine,” she said. “And the opioids themselves also affect your mood – negatively – causing depression. That can drive a person to take more drugs, along with the change in dopamine.”

Creed is also curious how chronic pain – what is often the reason a person is given opioids by their doctor – impacts the process.

“Chronic pain can change your mood. It impacts the brain in very complicated ways that we just don’t understand,” she said. “If you now put oxycodone on top of that, how are those effects going to be different?”

Despite her recognition for her research so far, to Creed, she has so much more to do.

“I’m just getting started.”

It’s like completing one layer in a very complicated puzzle.

“One of the main reasons people do this job – not for the money – this is the best part: even if it’s a more fundamental discovery that nobody else knows, it’s a pretty amazing feeling to be the first person to discover it. And then you try to figure out how it all works,” she said. “It’s not many people who get to work out puzzles for a living.”

Creed admits it can get frustrating when experiments are failures, but research scientists must have thick skins.

“Any sort of successful scientist – their number one skill is to be resilient,” she said. “I’m still learning.”

That learning began more than two decades ago right here in Chatham-Kent.

min=-13.0

max=209.0

[…] The Chatham Voice full article > […]

[…] Author : The Chatham Voice full article > […]