Chatham native Ruth Rappini knew her father spent most of the Second World War locked up as a prisoner, but it wasn’t until after he died that she really came to understand what he endured.

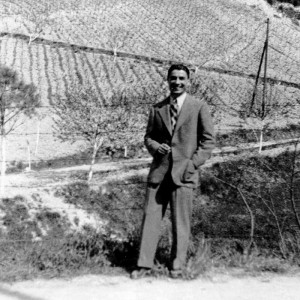

Her father, Vittorio Rappini, told the family little of his time in the Italian Navy as a submariner, and didn’t want to discuss his time in prisoner of war camps. He remained quiet about it all throughout his years living in Chatham after emigrating from Italy.

But two years after Vittorio died from a brain aneurysm in 1994, Ruth received a plain brown envelope that would start filling in the blanks and ultimately lead her to write a book about her father.

baCK-video-30sec from Chatham Voice on Vimeo.

>

“It’s a story that had to be told. It is so unique from different wartime stories and immigration stories,” she said. “He wouldn’t talk a lot about it (his war experiences). I only knew bits and pieces.”

What Ruth did know was Vittorio, at the brash age of 17 was a crewman on an Italian submarine. His sub was shelled and sunk in 1940, with most of the crew rescued by the same ship that fired on them.

She also knew he spent the rest of the war in various POW camps in England and the U.S.

But when that envelope arrived, with it came enlightenment. Ruth said her aunt sent the package, which was filled with wartime letters her father had written to his mother while he was a POW.

“I knew he’d been in these places, but no idea where exactly,” she said of the POW camps. “I can read Italian and got the gist of what they were about and I thought, ‘Oh my goodness, there’s a story here somewhere.’”

Ruth said her father joined the navy seeking adventure.

“He was 17 on a submarine. He didn’t understand the danger and was out for adventure,” she said. “But a lingering bitterness (against Italian dictator Benito Mussolini) came out in his letters during his time as a prisoner of war.”

In October of 1940, depth charges from the destroyer HMS Firedrake forced Vittorio’s submarine, the Durbo, to the surface where the crew surrendered.

“The Firedrake shelled the sub, but also saved the crew. In fact, they treated them very well,” Ruth said.

Vittorio spent time in prisoner of war camps in England before being transferred across the Atlantic in late 1942.

At the same time, Ruth said the Firedrake was on convoy duty, headed west across the Atlantic as well. It never made it to North America. While Vittorio and other members of his submarine crew survived the war, only 27 members of the Firedrake’s crew were pulled from the icy waters of the Atlantic after a German U-boat torpedoed the ship.

Ruth said her father learned of the Firedrake’s sinking and was quite upset.

Vittorio landed in Halifax at Pier 21 – he would do so again some years later – and was transferred to a POW camp in Tennessee, Ruth said.

“The prisoners were treated very well in the U.S. camps,” she said. “In Britain, they were actually starving because the British didn’t have many supplies. After they went to the States, they were well fed.”

Life in the U.S. camps may have been good, but Ruth said her father suffered a great deal of mental stress, worried about what was going on at home. As new Italian POWs entered camp, he and others would hear new horror stories of Mussolini’s rule.

Finally, the war came to an end. For Vittorio, it was back to Italy, working with the U.S. Army. Ruth said her father taught himself English while a POW and went home to Bologna and helped with the United Nations rehabilitation and relief effort and later as a finance officer.

But Vittorio soon wanted to leave his home country and got a work visa that saw him head towards Boston. But Ruth said things didn’t work out, and her father had to return to Italy.

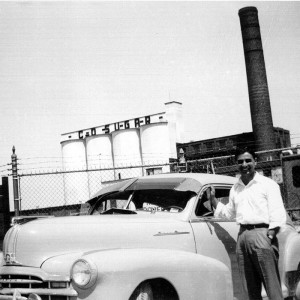

But an Englishman he met in Boston had a son who worked in the Canadian government, Ruth said, who advised him the Canada & Dominion Sugar Company in Chatham was looking for workers.

In early June of 1951, Vittorio again came to Halifax, through Pier 21, to begin life in Canada, working in the beet fields for four months. Ruth said her father completed his one-year commitment to the government by working on a pig farm.

From there he went on to land a position at Eaton’s as a radio and television repairman before shifting over to Union Gas as a labourer and later as a salesman.

Through all this, he met Lillian Beaudette, a Chatham schoolteacher, and fell in love. They settled down in Chatham and raised a family before eventually moving up Highway 401 to London where Lillian still lives today.

Ruth’s book, “Vittorio’s Journey: An Italian Immigrant’s Story,” came out in late October. It is available through Chapters/Indigo, Ruth said.

For more information, visit www.vittoriosjourney.ca

.