By Pam Wright, Local Journalism Initiative

The headline in the July 4, 1918 edition of the Thamesville Herald read: ‘Influenza on the German Front.’

It was a summer story, featured on the page with the every-day happenings of small-town Ontario.

It ran beside other stories with more alarming headlines such as ‘Tons of bombs upon the Huns’ and ‘Great smash by Allies into German Lines.’

But it wasn’t until the seasons changed that the pages of Kent County’s newspapers began to openly report about the scourge of the Spanish Flu.

On Nov. 28, 1918, The Herald’s front page featured an article entitled, ‘First Death from Influenza.’

The story said that Thomas Earl Laing, 26, had passed away from the flu, leaving behind a widow and three small children.

Laing had been Thamesville’s barber for just over a year, having purchased the business in 1917. He was buried in Ridgetown.

Earlier, in the Nov. 21 edition, the paper had said there were 35 cases of influenza in and around Thamesville, but the paper did not specify the illness as Spanish Flu.

However, it did say the virus was thought to have spread as the result of a dance in the community attended by 150 people.

An editorial comment in the same edition asked for sympathy from The Herald’s readership.

“Owing to sickness, The Herald is very much handicapped. We ask the kind indulgence of our subscribers and customers until we can get things adjusted again.”

In Dresden, things became so dire because of the Spanish ‘Flue’ that the Catherine McVean chapter of the IODE organized a travelling soup kitchen to help feed the ill.

Records taken from 1918 IODE meeting minutes lamented the fact that with the war over “society had earned a rest from death,” but was then bombarded with a “new wave of death.”

The Chatham Daily Planet was far more detailed in its reports about The Spanish Flu thanks to good record keeping by the City of Chatham’s department of Public Health.

But there was a complicating factor.

It is difficult to predict when Spanish Flu was first officially identified because a typhoid fever outbreak struck the city at the height of summer.

On Aug. 6, 1918, the paper reported that Chatham’s two hospitals were “congested with patients suffering from typhoid fever – over 130 cases in city.”

The story went on to say people were sleeping in tents on hospital grounds, as well as being housed in corridors and screened-in porches around the city.

It said about 80 patients were from rural areas.

A case of smallpox in Wallaceburg was also reported.

Over the course of the next couple of months, officials grappled with illness and the matter was exhaustively investigated through testing of water wells and milk.

On Aug. 19, Dr. T.L. McRitchie, Chatham’s Medical Officer of Health, came to the conclusion not all of the illness was caused by typhoid.

Reports in the Planet’s Aug. 23 edition reported that Chatham was to be quarantined, but officials said that was not the case and that the people spreading the rumour could be prosecuted.

However, people still continued to fall ill. As a preventative measure, some 1,500 residents were inoculated against the disease.

Still, no one spoke of the flu.

On Sept. 18, on page 3, massive outbreaks of the Spanish Flu – including many deaths – were reported in New England.

The Sept. 30 edition of the Planet reported Canadian influenza outbreaks in Newfoundland and Quebec with the first known death.

But Kent County officials attempted to downplay the severity of the flu in the paper, saying illness in the city was not the ‘Spanish Grippe menace.’

Just a troublesome cold, officials said.

On Oct. 4, the news finally hit the Chatham paper’s front page with the headline ‘Outbreak of Spanish Flu Threatening.’

Scores of school children were ill, the paper said, with schools only half full.

The Medical Officer of Health said strong, preventative measures needed to be taken and any workers with symptoms who handled food, had to go home immediately.

Yet, local authorities continued to downplay the severity of the disease.

On Oct. 10, the main headline said 600 local children were out of school and that the Spanish Flu had reached ‘all corners of the earth.’

The disease began its fatal sweep across Kent County and quarantines were put in place.

The Oct. 16 headline said public schools and a Chatham high school were closed because of an outbreak of influenza.

A day later, the board of health closed theatres, dance halls and a business college. Officials also forbade all lodge meetings and public gatherings.

Billiard hall owners were told to limit patrons or risk being shut down.

On Oct. 18, 22 deaths were recorded in Chatham in a 24-hour period, 15 the previous day. Nearly 700 people, including health-care workers, were said to be sick.

Local doctors were reported to be working ‘day and night’ and one, Dr. Stanislaw Brisson, perished from the flu on Oct. 20.

During this time, Ontario’s Board of Health sent out more than 10,000 doses of flu vaccine as a means of prevention.

On Oct. 23, The Planet reported that Bothwell was hard hit by the virus, as all doctors, except for one in Florence, was sick.

Bothwell’s drugstore was also closed, as the owner was ill.

Across Kent, entire families were confined to their homes.

Near the end of the month, The Planet said the virus was running rampant in the rural areas, and during this time churches were closed.

Board of health members said what would today be called “lockdown,” contributed ‘”in large measure” to combatting the Spanish Flu.

The ban was partially lifted Nov. 4, and fully lifted Nov. 9.

On Nov. 11, people spilled into the streets to celebrate the end of the First World War.

Some critics said the event caused further spread of the disease.

In a report on Dec. 3, McRitchie estimated the Spanish Flu had hit some 2,200, but the number of deaths was unknown.

The province said 5,623 people died in two months in the fall, but admitted reports were incomplete.

Then more cases surfaced.

On Dec. 17, The Planet reported influenza was again spreading in the county, and a day later, it said a family in Dresden had lost two loved ones.

Spanish Flu continued to strike people in all areas of the county.

On Dec. 28, an entire family in Raleigh Township was sick with the flu, and on Dec. 30, Rev. T. J. Hamilton, the Anglican Church rector in Ridgetown died from influenza.

People where told to only use services such as the telephone for emergency purposes.

In the days before government-supported healthcare, many people did not see a doctor or go to a hospital because they could not afford it.

So they died at home, often without an exact cause of death.

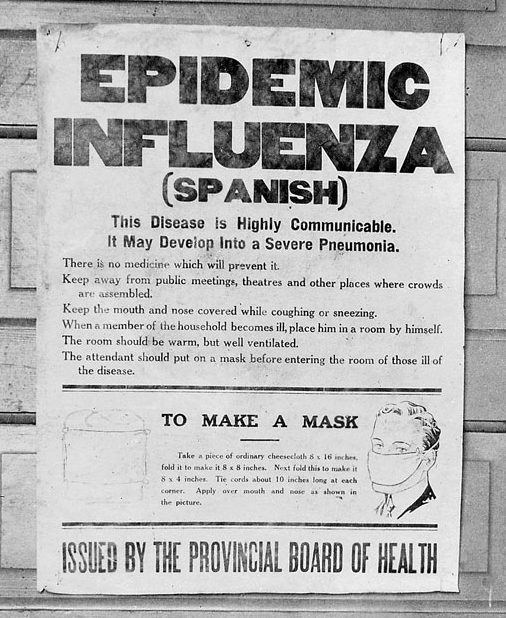

It remains unclear where or not local citizens were instructed to wear masks, but in the Western provinces –with Alberta being especially progressive – governments mandated citizens to wear them.

With thanks to Deborah Kennedy, Marie Carter, Jerry Hind, Jennifer Hinks-Cartier and Jim and Lisa Gilbert.

• The Thamesville Herald