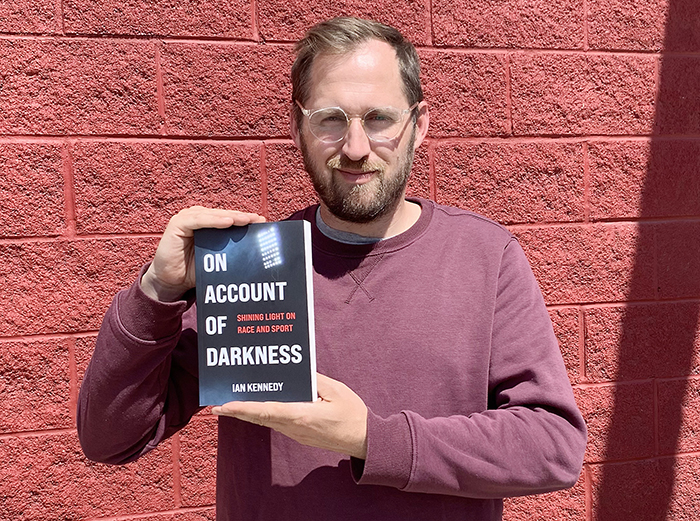

Chatham-Kent writer and educator Ian Kennedy has written his first book, “On Account of Darkness,” a recounting of stories of athletes and the relationship between race and sport in North America.

Ian Kennedy’s passion for sports and writing, combined with some added spare time due to a global pandemic, led to the local educator penning his first book, “On Account of Darkness.”

Each chapter uses the story of a local athlete to shine a light into the dark corners of racism in sport.

“We have this rich history of Black, Indigenous and Japanese-Canadian athletes getting into sport, but it was not easy. There were so many barriers in place that we don’t talk about,” Kennedy said. “This book looks at all those social issues through the lens of sport. It’s showing that sport, just like everything else, played a role in holding and dividing the lines. But it also gave some of those athletes the opportunity to overcome and escape those barriers because of their talent.”

Kennedy, an educator and a life-long Chatham-Kent resident, said his writing for his website, CKSN, as well as other outlets over the years exposed him to stories of racial injustice on the playing fields and in the rinks.

“I came to discover stories about athletes and teams that I really hadn’t grown up knowing,” he said. “Whether that was the Chatham Coloured All-Stars, or the Wakabyashi family and people like that. And when the pandemic hit, live sports stopped, so I had time to explore those unique stories; the ones we hadn’t always heard in Canada, whether it’s about Black, Indigenous or Japanese-Canadian athletes in Canada, and put together the stories that I had started into a larger project.”

The Chatham Coloured All-Stars are the first all Black team to win a provincial title in Ontario. They did so in the 1930s, facing severe racism on the road. People such as Fergie Jenkins Sr. were on that club.

The Wakabyashis came to Ontario during the Second World War, as Japanese-Canadians who were interned in the province during the war. The family moved to Chatham in 1950, and their children Herb and Mel, became local sporting legends, excelling in multiple sports.

Initially, Kennedy said he planned to self publish, but circumstances changed that.

“I was actually sitting in the Black Mecca Museum here in Chatham researching for my own project, and Sam (Samantha Meredith, executive director of the museum) got an e-mail from a publishing company asking, ‘Is anyone locally writing about the Chatham Coloured All-Stars?’ She called over and said, ‘Ian, you’re doing this,’” he said. “Within five days, I had a meeting with Tidewater Press and was signed.”

As Kennedy researched his subjects, he learned just how rampant racism was in this part of Ontario, despite the fact we were once the terminus of the Underground Railroad.

“In Canada, we portray ourselves as this multicultural country that doesn’t have the same issues as other countries in the world. That’s really not true,” he said. “We have the same history of slavery and Residential Schools and Japanese internment. We kind of gloss over that.

“Those issues are still pervasive in sports today. Some of these things have gone away, but the truth of the matter is the lasting effect, the generational trauma, the barriers that were put in place in the ’30s, ‘40s and ‘50s are still impacting athletes today.”

Kennedy said racism in sports stopped careers in their tracks, or before they even got started.

“If your grandfather wasn’t allowed to skate in an arena because he was Black, then he wasn’t as likely to teach his kids to play,” he said. “And they didn’t teach their kids to play hockey.”

And while some may have never taken to the ice, others had hockey used against them in multiple ways. Kennedy said he was bothered by the role that hockey played in Residential Schools.

“Hockey was introduced to make Indigenous youth feel more Canadian and for them to identify as Canadian rather than as their fundamental identification as Indigenous persons,” he said. “And then it was used as a discipline. When Indigenous youth started loving the game, it could easily be taken away.”

Kennedy hopes “On Account of Darkness” makes people think…and talk.

“Hopefully the book kind of gives the opportunity to begin the discussion of who we actually were, where we actually are and where we go next,” he said.

“We have a long way to go, definitely. We’ve come a great distance, but the same systems that oppressed and the same systemic issues are still there, they are just right under the surface,” Kennedy added. “To ignore the truth of our history is to foster the cycle to continue.”

As for what the future holds for Kennedy, the immediate future sees several local events promoting the book. They start with a book signing and reading at Turns and Tales May 28 on King Street West in Chatham. He follows that up a week later with a signing and launch party at Sons of Kent, and a talk and another signing June 11 at Buxton.

Following that, he said he has other books in the planning stages. He is still writing for The Hockey News and Yahoo Sports.

And he’ll continue to do his part to battle racism.

“It’s not enough to not be racist, we have to be actively anti-racist.”

Racist sentiment is typically handed down generation to generation, regardless of color or creed. If it’s deliberate, it’s something I strongly feel amounts to a form of child abuse: to rear one’s impressionably very young children in an environment of overt bigotry — especially against other races and/or sub-racial groups (i.e. ethnicities).

Not only does it fail to prepare children for the practical reality of an increasingly racially/ethnically diverse and populous society and workplace, it also makes it so much less likely those children will be emotionally content or (preferably) harmonious with their multicultural/-racial surroundings.

Children reared into their adolescence and, eventually, young adulthood this way can often be angry yet not fully realize at precisely what. Then they may feel left with little choice but to move to another part of the land, where their race or ethnicity predominates, preferably overwhelmingly so.

If not for themselves, parents then should do their young children a big favor and NOT pass down onto their very impressionable offspring racially/ethnically bigoted feelings and perceptions (nor implicit stereotypes and ‘humor,’ for that matter). Ironically, such rearing can make life much harder for one’s own children. …

While there’s research through which infants demonstrate a preference for caregivers of their own race, any future racial biases and bigotries generally are environmentally acquired. Adult racist sentiments are often cemented by a misguided yet strong sense of entitlement, perhaps also acquired from one’s environment.

Maybe this social/societal problem could be proactively prevented by allowing young children to become accustomed to other races in a harmoniously positive manner. The earliest years are typically the best time to instill and even solidify positive social-interaction life skills/traits into a very young brain/mind. And I can imagine this would also be particularly important to achieve within one’s religious community.