Students across the St. Clair Catholic School Board gained greater insight into the meaning behind Orange Shirt Day as members of the Bkejwanong (Walpole Island First Nation) brought their knowledge and stories on treatment of Indigenous children at Residential Schools to Our Lady of Fatima School.

The date of Sept. 30 is recognized as National Orange Shirt Day in Canada and the area First Nations members visited more than 20 schools across the St. Clair Catholic Board to bring their message of resilience with storytellers, a visit from two horses and representatives from TJ Stables who told students stories about the Anishinaabe Spirit Horses, and traditional drummers and singers.

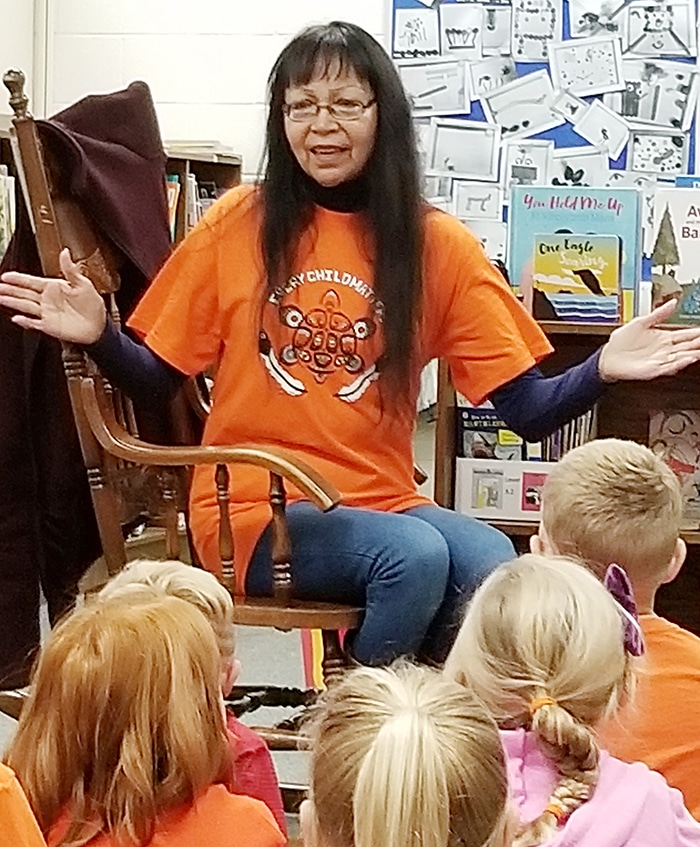

In an age-appropriate way, students were told stories of what happened to children sent to the Residential Schools. Younger students were read children’s books, written by Indigenous authors who experienced such schools, by Bkejwanong First Nation Public Library librarian and storyteller/writer Linda Lou Classens, including the original story behind Orange Shirt Day.

Indigenous Education Lead for the school board, Cortnee Goure, said the event was part of the Indigenous education pursued across the board and the main theme was to teach students about the resilience of the children who were forced to ignore their Indigenous culture and language while at Residential Schools.

The First Nation elders, including Bkejwanong knowledge keeper Cecile Issac Jr. who was at the event, are bringing the language, culture and traditions back to their young people.

Classens, whose parents both attended Residential Schools, told the story of Phyllis (Jack) Webstad, who lived with her granny on a small reserve in British Columbia and was excited to go to St. Joseph Residential School and have friends to play with. Her granny saved up her money to buy Phyllis something special for school, which was a shiny orange shirt to wear on her first day of school.

The storyteller dramatizes the tale of what happened to Phyllis when she arrived at the school, where she was stripped of her orange shirt, her hair was cut, and she was not allowed to speak her language or practice her cultural traditions.

“She realized that it didn’t matter if she was tired, sick, hungry or sad, she had to rely on herself,” Classens said. “It was like she didn’t matter. And that’s when I say, ‘Every child matters,’ and that’s the message I try to get across to the kids.”

Classens said Webstad spoke at a conference about how, at the age of six, Residential School affected her feelings of self-worth, and she worked hard to keep her life, family and traditions together, and the Orange Shirt movement was born in 2013.

“That’s what the Orange Shirt story does; it brings attention to the fact that there were great wrongs done to our people,” Classens noted, stripping them of their culture. She said the physical and sexual abuse is a story that is difficult to tell, but is a part of the overall story.

“It’s really good that the Catholic school system is really bringing in our people and talking about dance and culture and Native language and traditions and what’s really coming out of this is the resilience part, which is yes, we went through a horrible time but people still managed to hold on to their identity.”

She said one thing that really suffered was the loss of language, but there are people in the community like Ed Taylor who is bringing back the Native language to Bkejwanong First Nation.

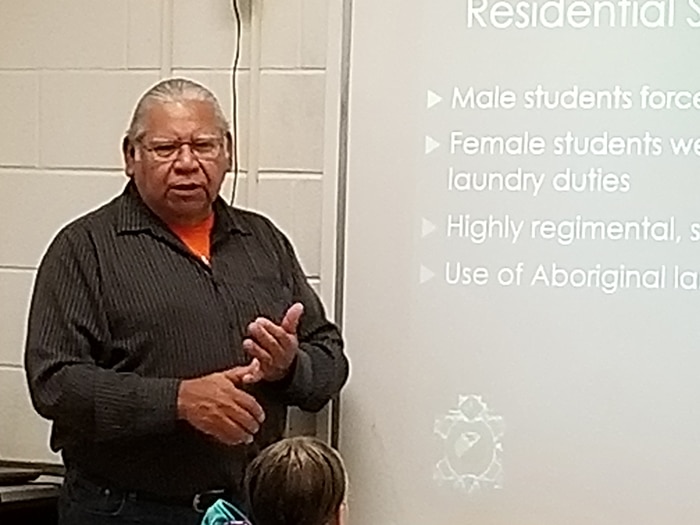

Issac, who told the story of what his father endured at the Residential School in Brantford, said his father moved them to Detroit to avoid the oppressive ways in Canada. He moved back to the area in 1962, but he missed out on the opportunity to learn to hunt and fish and be free on Walpole Island.

He agreed Taylor is an excellent teacher of the language.

He agreed Taylor is an excellent teacher of the language.

“In the whole process, Dad has been able to maintain a lot of his language and with language comes culture and with culture comes ceremony,” Issac said. “With the disconnect from culture and ceremony, you see the issues with alcohol and family violence, but then you reach a point you say, ‘Why?’ and there has been a sort of awakening in a lot of our people. You don’t have to do that anymore. Here’s what you need to do and that’s what happened with my family.”

Since 1971, Issac’s journey has led him back to family, a healthier lifestyle and culture and ceremony, learning to “walk the walk.”

“The more I learn from all cultures, and that’s the good thing about it, in medicine wheel teaching, it teaches about equality and the gifts that all cultures have, so we start to bring that in and we start to become a more enriched person and you have a more enriched viewpoint of humanity, and now from my Indigenous perspective, I can bring that forward and take things with that knowledge base,” Issac noted.