Editor’s note: This is the final story in a three-part series on human trafficking in The Chatham Voice.

After many years of imploring the Canadian government to investigate the murder and disappearance of Indigenous women across the country, there will finally be a National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls.

The announcement, made earlier this month, is an issue followed closely by David Maris, an artist and activist originally from the Blenheim area. Through his art, which he calls neo-political expressionism, Maris created a series of paintings on canvas that he calls flags, which depict his anger with the violence against Indigenous women and the injustice of a government that has been called out internationally for its poor record on addressing human rights violations.

His flags are currently on display in the Blenheim United Church as part of an exhibit that will eventually make its way to Switzerland.

Two years ago, Maris said he was part of an international group of artists, Global Discomfort, producing activist art. When the United Church, nationally, put forward a resolution calling for a public inquiry into the murdered and missing Indigenous women, he called them.

“I contacted them about working with them and having shows that could highlight the issues,” Maris said while in Blenheim to visit his sister. “I give a nod to the United Church that they have taken such a bold and progressive step.”

Although he spends most the year in Switzerland with his wife and family, the 60-year-old artists travels extensively for exhibits, and makes no apologies for the dark and violent nature of his painting.

“My work is outspoken. I’m not passive and my work is very aggressive and violent (with the flags) and the Indigenous community is onside with that. A woman spoke up that lost a member of her family and said that passive has gotten them nowhere, and if it takes something as aggressive as this to be heard, then she was OK with that,” Maris said.

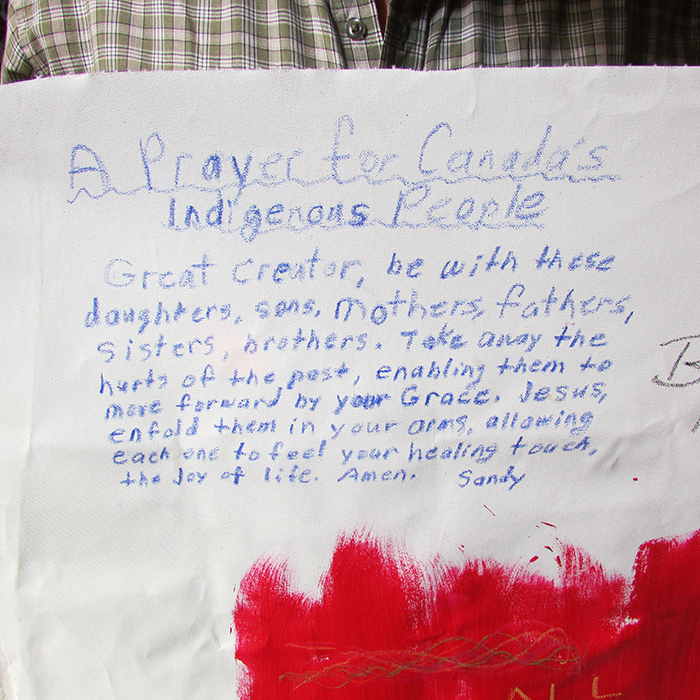

The flags, with dark red and black streaks, numbers, and the word “no” on them, along with small crosses, hold the names of victims and some of the words from their families.

“The pieces themselves are raw in content; they are not delicate, produced in a manner that is indeed as raw and violent as the subject itself. I read or listen to the personal stories, and my emotions and anger come out on canvas,” Maris said in his explanation of his work on the flags. “I use a lot of numerical representations, some factual and others not, as we reduce beautiful people to numbers, to statistics; not to the life they represented.”

Maris believes that if we as individuals speak out against the issue of violence and demand action from the government, that society can begin to heal and truly be free.

Since 1980, official RCMP statistics show 1,200 missing or murdered women and children, but the Native Women’s Association of Canada puts that number closer to 4,000. In 2015, Maris said the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women ruled that the Canadian government had committed “grave violations” of the human rights of Indigenous women by not doing more to address the epidemic violence against them.

With the exhibit of his flags, Maris puts the victims and their families in the forefront, referencing Mary Ann’s Flag, a victim of domestic violence and murder from the Zhiibaahaasing First Nation of Manitoulin Island, Claudette’s Flag that quotes the frustration of her father still searching for his missing daughter, and Cindy Gladue’s Flag, in memory of the Edmonton woman who bled to death and whose accused was acquitted after a court trial that re-victimized her and her family.

In Ontario, the government has finally introduced an anti-trafficking strategy that acknowledges that violence affects Indigenous women more than any other group in our society and includes Indigenous-led approaches specific to victims’ services and supports. The three year roll-out of the $72 million in promised funding attached to that strategy has yet to be announced.

The Ontario Native Women’s Association, in a report on sex-trafficking released earlier this year, stated that while there is a scarcity of accurate information regarding the trafficking of Indigenous women and children, “at the same time we know that Indigenous women and girls are vastly and disturbingly over-represented in all human trafficking.

“The root causes of violence against Indigenous women are systemic, rooted in structural and social inequalities and the ongoing and historical processes of colonization,” the report said. “Ending trafficking is essential to the overall eradication of violence against Indigenous women and girls.”