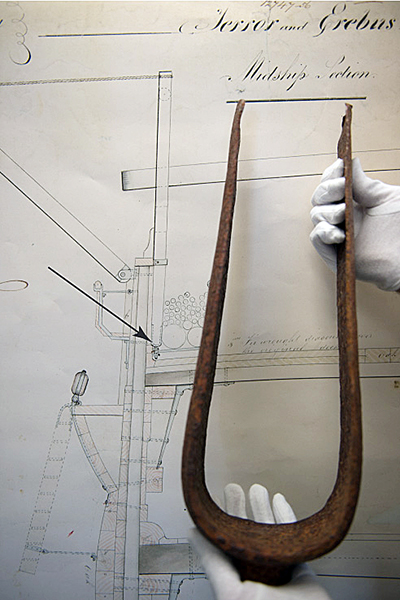

Chatham native Doug Stenton showcases the fitting he and a team discovered in September on an island in the Victoria Strait. It led searchers to one of the lost Franklin Expedition vessels. (All photos courtesy Government of Nunavut, Department of Culture and Heritage)

Last week’s blustery weather chilled most of us to the bone, but it was a breath of warm air to Chatham’s Doug Stenton.

Then again, for the past 23 years, Stenton has called Nunavut home.

The 61-year-old archaeologist is in town on leave after a wild fall that included his key role in the Franklin Expedition discovery which made headlines around the globe.

He’s the director of heritage for Nunavut’s department of culture and heritage. For the past six years, Stenton was heavily involved in the hunt for the lost expedition, which became trapped in heavy ice while searching for the Northwest Passage in 1846 and vanished. Subsequent searches revealed only hints of the location of the HMS Erebus and HMS Terror, Sir John Franklin’s ships.

Chatham Mazda from Chatham Voice on Vimeo.

In 1992, the federal government declared the shipwrecks to be national historic sites, despite no one knowing where they were.

The serious effort to track them down began in 2008, Stenton said.

Parks Canada initiated the modern search for the vessels, and Stenton quickly got on board.

He said the hunt began with a great deal of planning and research. That was followed by short periods of fieldwork, as the search took place in the summers in Nunavut.

He said the hunt began with a great deal of planning and research. That was followed by short periods of fieldwork, as the search took place in the summers in Nunavut.

“The summer time is a very narrow window of opportunity. You have to hope the ice melts,” Stenton said. “It’s only a matter of weeks.”

For six years, the searchers proceeded in this manner. And finally in early September, it was Stenton who suggested they search in the fateful spot. Chopper pilot Andrew Stirling took archaeologists Stenton and Bob Park, as well as hydrographer Scott Youngblut to a small island south of where they’d hoped to be searching. Inclement weather had forced the change.

Some say what happened was blind luck, but Stenton said the area they searched was part of their plans all along.

“We were going to that island anyway. It was as much as us sticking to our plan that we developed back in 2008 than anything,” he said.

The weather this summer did push them south, however.

“The conditions in the field were different than the previous five years, mainly in terms of ice cover further north,” Stenton said. “We spent a lot of time in the southern parts. I was looking over maps and charts, and each day we were doing helicopter and walking surveys.

“We had planning meetings every morning. On that particular day, we were informed again we weren’t able to go further north. The island was among the next that we opted to survey.”

Of all the expertise on board the helicopter that day, it was the pilot who made the discovery that would ultimately lead the search teams to a nearby shipwreck.

“In some areas, the pilots will do other things. They’re not obligated to do archaeology, but we worked with Andrew a couple of years ago and he was very interested,” Stenton said. “After we set down, we started doing normal procedures…Andrew and Robert Park from the University of Waterloo started walking near the water’s edge. He (Stirling) found the iron fitting.”

That fitting weighed about 4.5 kilograms and had Royal Navy markings on it.

The in-water Parks Canada search shifted to near the island, and sonar soon revealed a nearby shipwreck – the Erebus.

They had found a national historic site and solved a 168-year-old mystery.

For Stenton, it marks the high note of his career. He’s thinking about retiring in about a year and maybe moving back to Chatham.

“I’m not going to stop doing archaeology,” he said. “I will be publishing my research with my colleagues. I’ll be pretty busy.”

He also holds adjunct status at Trent University and the University of Waterloo, so teaching could be in his future as well.

Coming back to Chatham full time would be a big change for Stenton. Not only have he and his wife lived in Nunavut for the past 23 years, he’s been doing archeological research up there for more than 34 years.

“I was completing my undergraduate degree at the University of Windsor in 1980 and had a chance to go up to Frobisher Bay to do some work. We spent a summer up there and sort of got hooked,” he said.